Public health organizations have stated that social distancing is one of the most effective ways to reduce the spread of the coronavirus. Social distancing entails active separation from in-person social gatherings: avoiding parties, public transport, crowded streets, and any other source of fun. When people are forced to go around others, the CDC offers specific guidelines about how to keep yourself and others safe: one of these guidelines is to keep six feet away from others. While this seems like a simple recommendation, it has specific, geometric implications…

Tesselations

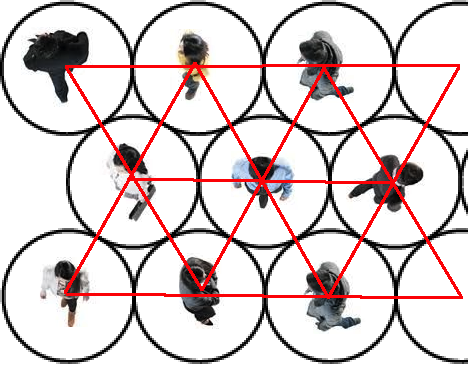

Staying six feet away from people is solid advice. However, with the help of a little geometry we can do even better. Here’s a useful way to reformulate the question of physical distancing: given a finite number of people in a finite area, how do we maximize the distance between each person? Think of each person as a point in space: the average distance between people is simply the sum of the pairwise distances between people divided by the number of pairs (the numerator is n!/2). A naive algorithm to maximize distance is to randomly place people in space (while maintaining 6 feet from all neighboring people), measure the pairwise distances, and see if it’s better than any of our previous configurations, and repeat. This is an inefficient algorithm. A better approach would be to think of people as vertices and the distances between people as edges: vertices and edges make shapes, so we can think of the problem as which pattern of shapes maximizes distance, or, conversely, which pattern of shapes fits the most vertices in the smallest area (keeping in mind that none of the vertices can be smaller than 6 feet). The image below represents a poor way to pack people into two-dimensional space, with many people violating the 6-foot rule:

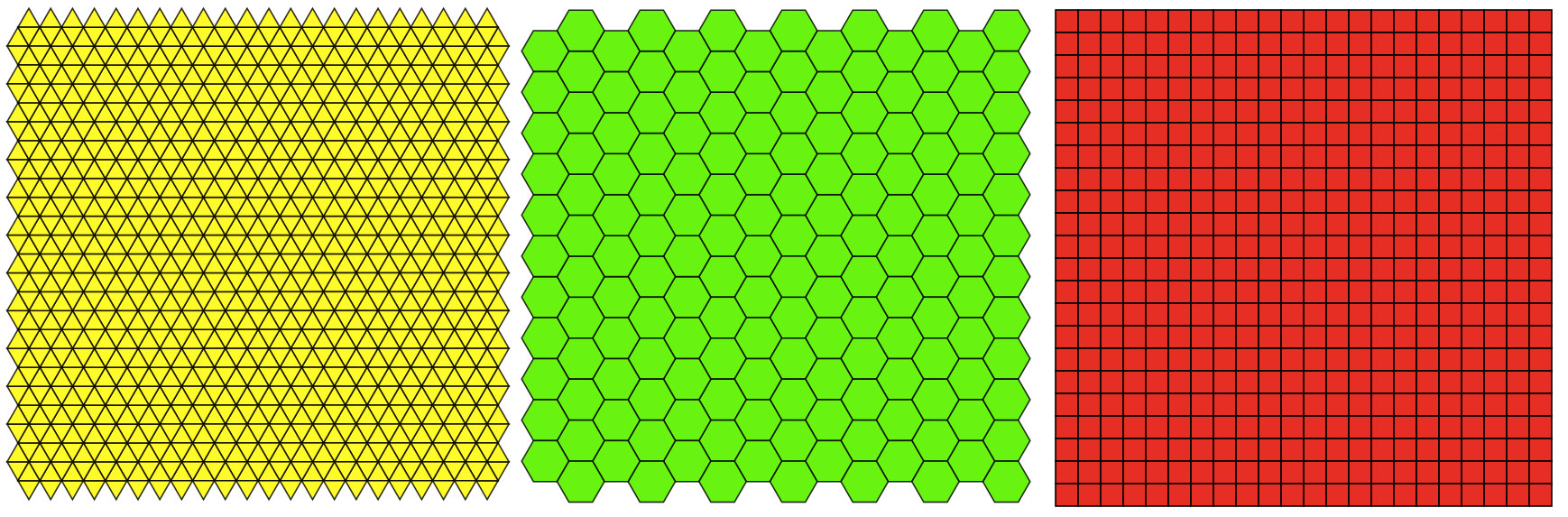

Let’s start off with something simple: filling up space using one kind of shape at a time. If you have some plane and want to tesselate it using only one kind of shape, there are just three shapes available to you: these are the three Euclidean tilings, shown below:

That’s right, only equilateral triangles, squares, or hexagons can fill a plane. Let’s compare these three shapes and see which pattern lets us pack in the largest number of vertices in the smallest area.

We can immediately conclude that hexagons are less effecient tesselations than equilateral triangles: for every hexagon, you can drop a new vertex in its middle, draw a new edge between this vertex and every existing vertex, and create six triangles: That’s right, given the same amount of space, hexagons have 6 vertices and triangles have 7. So now we just have to compare squares with triangles. One way of thinking about the problem is to calculate the area of each shape and divide the area by the number of vertices. For a square, given an edge length of 6, this is 6^2 = 36 / 4 = 9. An equilateral triangle, on the other hand, is sqrt(3)/4 * 6^2 = 15.59 / 3 = 5.12. Because 9 > 5.12, we can conclude (with some, albeit informal confidence) that equilateral triangles are better tesselations for maximizing distances between people.

This makes intuitive sense too: imagine extending a stick six feet away from your body and drawing a don’t come inside here circle. Then pack these circles together efficiently (hexagonally). If you then drew edges between the centers of adjacent circles, you’ll get a triangular tesselation! I’m not going to rigorously prove that other combinations of shapes (squares plus triangles, rectangles mixed with parallelograms…) can’t be more efficient than triangles, but keep in mind that every line you could draw between the edges of a triangle would already be the minimum permitted edge length, whereas you could draw a line of greater length than 6 between opposite edges of a square with side length 6…

Reality

Ok, so given a very large space and a large number of people, a triangular tesselation is our best bet for maximizing social distance… but what about real life, where spaces come in all sorts of shapes and sizes? What about a sidewalk, where only a few people might fit from end to end: if a group were walking, should they fall into a triangular pattern, or a square pattern (or something else)?

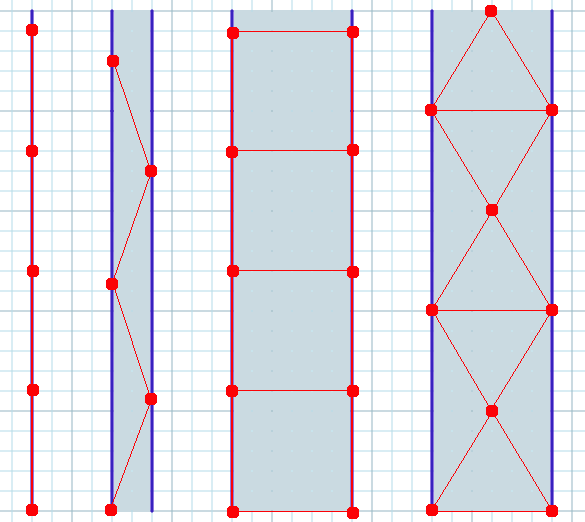

Well, to simplify this problem again, let’s say that you were walking in a group down a very narrow sidewalk. In fact, let’s say that the sidewalk was so narrow that it has only one dimension. In this case, you should walk exactly 6 feet behind the person in front of you. But let’s say that the sidewalk is 2 feet wide. If we imagine that the person in front of you is hugging the right side of the sidewalk, you should walk on the left side, keeping 6 feet apart from them but only 5.66 feet behind them relative to the length of the sidewalk (remember the Pythagorean theorem).

What happens, then, when the width of the sidewalk expands to six feet? Well, at exactly six feet, you can begin packing in squares of people. If a sidewalk is 600 feet long and 6 wide, then you can pack in exactly 100 squares. However, there aren’t 400 vertices, there are 400 / 2 + 2 = 202 vertices.

The math for a triangular tesselation is a little trickier. If you start drawing triangles in hourglass patterns, then one “hourglass” contains 5 edges and occupies 10.39 units of space along the line (remember the Pythagorean theorem!). That means you can only pack in 600/10.39 = 57.75 “hourglasses” of triangles along the sidewalk. However, the hourglasses don’t add edges at the same rate as squares: like squares, the total number of “outer” edges increases by 2 for each hourglass added, the the hourglasses get an extra vertex at the neck of the shape: (57.75 * 2 + 2) + 57.75 = 175.25 vertices in the hourglass pattern.

When stuck to a smaller rectangle-ish space, squares are better than triangles. However, as soon as the space grows larger than the width of a few squares (larger than 12 or 18 feet) triangles become a better. In other words, in smaller more weirdly shaped spaces, the most efficient packing method is tricky. However, as your space becomes larger, you can become more and more comfortable that a triangular Euclidean tesselation is the way to go.

Conclusion

If we’re going to be living a world of social distancing, we should put some thought into how exactly we’ll be distancing ourselves and what that geometry should look like.